Navigare Necesse Est: a disaster dodged

Navigare Necesse Est

“From the CCA School of Hard Rocks

...lessons learned in pursuit of the Art of Seamanship”

By Chuck Hawley, San Francisco Station, July 2024

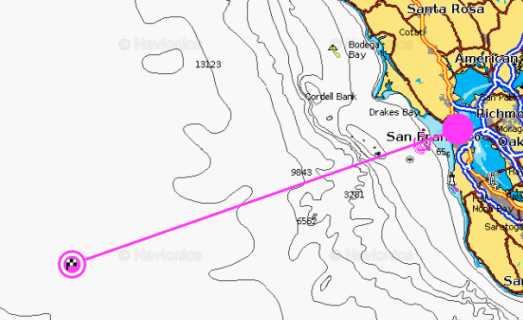

Many race organizers require a qualifying voyage of a certain length prior to allowing a vessel/skipper to participate. For that reason, I found myself heading out of the Golden Gate in April of 1982 on Collage, my Olson 30, in preparation for the 3rd biennial Singlehanded Transpac for a 300nm out-and-back romp. A vital lesson in seamanship, and a cold dose of reality, lay in store for me.

I had installed what was then a cutting-edge Loran-C in my Olson by Micrologic, made in Southern California. In 1982 it was possible to manufacture electronics in California and compete on the World Market. The ML-2000 was a wonder of sophistication because it could show your position in latitude and longitude, and navigate to waypoints, and it only cost $1500. In truth, I had borrowed it from the electronics display at West Marine in Sausalito (where I worked), and I hoped that no one would notice it was gone while I was on my two to three day voyage.

After being at sea for a little over 36 hours, I found myself 150 NM away from the Gate, whereupon I tacked Collage and headed for home. Optimistically, I had made a date with a young lady for the following night, so speed was of the essence. To ensure that I sailed the shortest distance, I entered a waypoint that was to the west of Southeast Farallon Island to ensure that I would sail the shortest distance, and set an arrival alarm with a 5NM radius to warn me as I approached the island. I set my autopilot on a course to the waypoint, again to shorten the distance and time.

For warmth and quiet, I dove headfirst into the weather quarterberth, with my head aft, and curled up in my sleeping bag. Collage happily reached along at 7 knots, and I fell sound asleep.

I woke up after what I assumed was a few hours due to the alarm coming from inside the boat. “Aha!” I said to myself, “I’ve entered the alarm zone and I’m close to the Farallones.” I struggled out of my berth, reached up for the companionway hatch, and slid it open. I had apparently overslept because it was pretty bright outside and the weather was glorious, with the wind blowing about 8 knots. As I gazed forward, under the boom and the foot of the jib, I was surprised that I couldn’t see the island up ahead. The weather was clear; where was the 400’ tall island?

As I pivoted around in the companionway, the island came into view, directly astern of me, perhaps three miles away. It lay directly behind Collage, bisecting the vessel’s wake. I could see no other solution to how I had managed to avoid the island other than perhaps there was a heretofore-unknown tunnel directly through the island that had allowed me safe passage. From my vantage point, there was no way that I could have missed it.

It took me several hours to shake off the feeling that I could have been killed due to a series of poor decisions that I had made which put me in this lethal situation. Among those decisions were the following:

- I entered a course into the autopilot towards a known hazard.

- I did not keep a proper watch.

- I relied on a single electronic device to alert me of a hazard.

- I let an appointment influence my decisions instead of good seamanship.

- I had intentionally isolated myself from the subtle sounds and signals that warn someone of danger (like the sound of surf on rocks.)

After the Aegean incident during the 2012 Ensenada Race, the question that inevitably came up was “how, with all of that electronic gear, could they have run into an island that’s clearly on the chart?” The same question was asked repeatedly after Vestas Wind ran up on Cargados Carajos Shoal in 2014. “How could it happen?”

Embarrassingly, I know from personal experience exactly how incidents like these happen. It starts with a decision that, deep inside, you realize is not good seamanship, since a less convenient or slower solution to a problem would be safer. But you elect to take the shortcut, to cut it too close, or to proceed too fast. It’s a conscious decision that leads you to take imprudent risks with horrendous consequences if you’re wrong. If we take enough risks, eventually, most of us will experience a completely avoidable incident, and we have no one to blame but ourselves.

The Cruising Club of America is a collection of passionate, seriously accomplished, ocean sailors making adventurous use of the seas. All members have extensive offshore boat handling, seamanship, and command experience honed over many years. “School of Hard Rocks” reports, published by the CCA Safety and Seamanship Committee, are intended to advance seamanship and help skippers promote a Culture of Safety aboard their vessels.