Search and Rescue Experience in Lake Superior

2024 Search and Rescue Experience in Lake Superior

Mark & Bev Lenci, M/V Friendship 4

We have decades of worldwide cruising experience, but those years never included being the primary vessel in a search and rescue (SAR) event. Then in one week, we were the primary vessel in three SAR events in Lake Superior.

In all three events, Friendship 4 served as the on scene coordinator for nearby efforts on shore, other vessels, multiple rescue coordination centers ashore, and in one case a USCG helicopter. All locations were remote with no cell phone coverage or nearby sources of assistance from shore. Robust communications by multiple means proved its worth. This article describes the SAR events as well as our lessons learned and observations.

SAR Event #1: Swimmer drowning, Wednesday, July 24

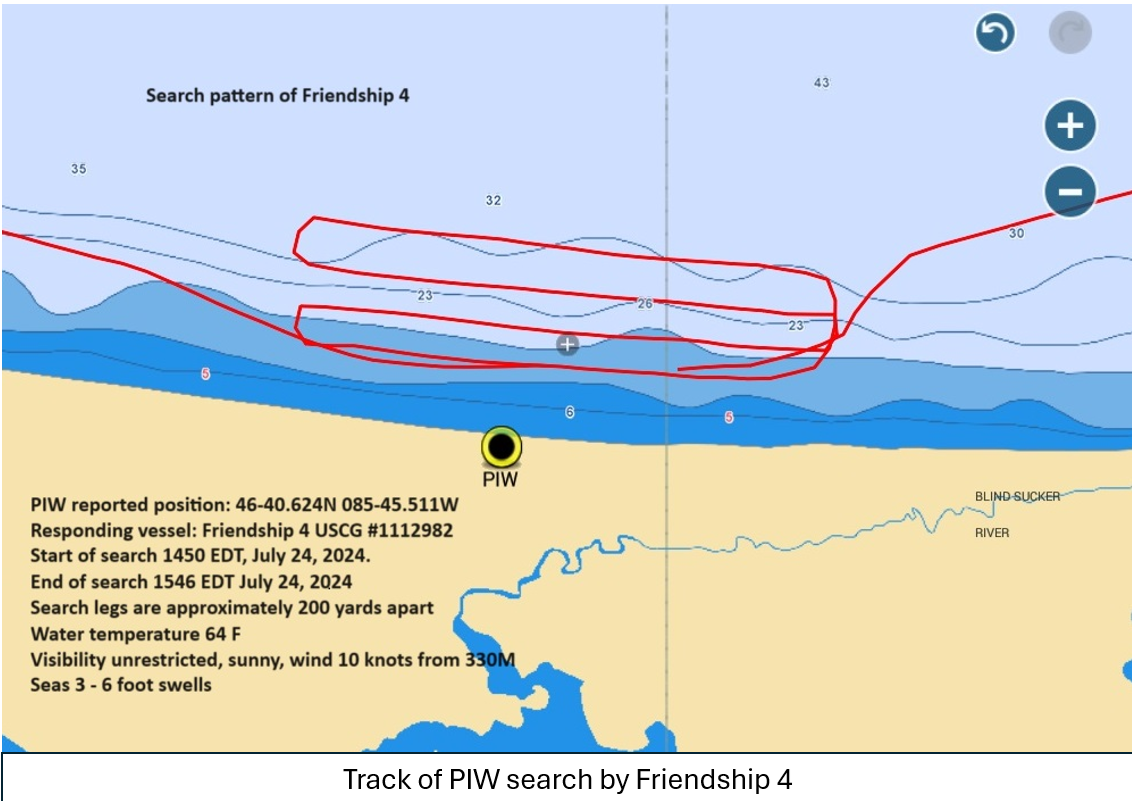

Friendship 4 was making a 90 NM passage from Sault Ste Marie to Grand Marais on the upper peninsula of Michigan. At 1:30 PM we were passing along Lake Superior State Forest about 5 NM off the shoreline. The US Coast Guard sent a Pan Pan message on VHF CH 16 regarding assistance for a swimmer that had been swept out into Lake Superior by the high surf. We checked the distance to the victim. We were 1 ½ hours away. We decided in view of the time to get to the scene, the high sea state and the very cold water, we would not be able to respond in time. We intended to continue our passage.

Shortly after the Pan Pan, the Coast Guard Sector Northern Great Lakes in Sault Ste Marie called Friendship 4 on VHF CH 16. They said based on AIS we were by far the closest vessel to the victim. They said local authorities could not launch small craft from shore due to the sea state and surf. We gave them our estimated time of arrival and they said we could arrive at least 45 minutes before the USCG helicopter. USCG boats could not arrive until the next day. We agreed to proceed to the scene at best speed.

There was no cell phone coverage along this shoreline. VHF CH 16 was marginal, so we established communication with the USCG sector headquarters with satellite phone. They briefed us on the situation as we proceeded to the scene.

We learned that the county sheriffs were in charge on the beach but their police radios could not use marine VHF CH 16. The sheriffs ashore would radio to their control center and that control center would talk to the USCG by landline. The USCG relayed voice traffic between Friendship and the sheriffs on the beach at the scene by satellite phone. Satellite communications were the means of communication most used and worked very well.

Upon arrival we established a parallel track search pattern starting as close to the beach as we dared and moving out 200 yards on each leg. Although the surf was high, it was a sunny day and the 22 foot height of eye on the flying bridge made us confident that our 3 lookouts would spot the person if they were on the surface of the water. We centered the search pattern where the family last saw the victim.

The USCG helicopter from Detroit arrive about 50 minutes after we had started our search. Friendship 4 discussed a recommended search pattern on VHF for the helicopter which the helicopter crew agreed to and executed. We made plans to use the USCG rescue swimmer if the victim was spotted rather than attempt to bring the victim aboard Friendship 4 due to the sea state.

The combined shore, Friendship 4, and USCG helicopter search efforts did not succeed in locating the victim. We ended all search efforts near sunset and proceeded to port. The victim’s body was recovered about 36 hours later after an extensive recovery effort regional authorities.

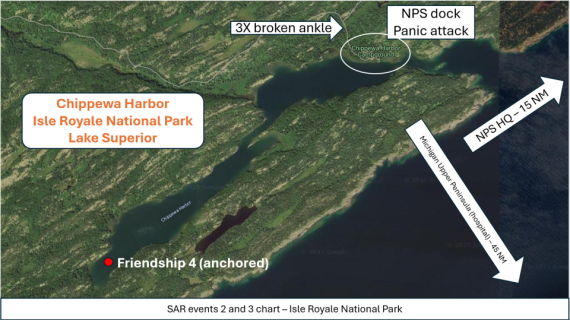

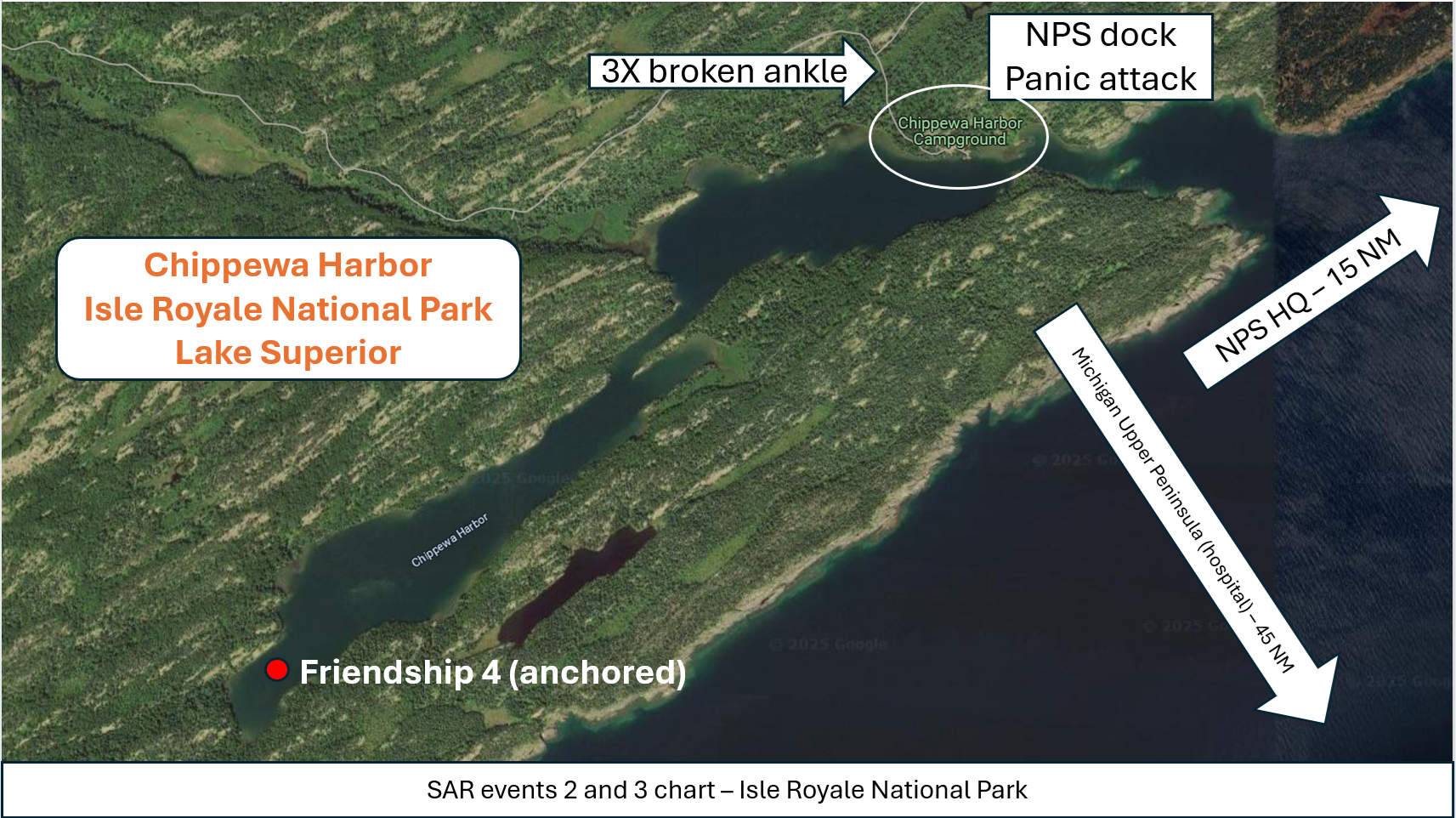

SAR Event #2: Severely broken ankle, Monday, July 29

Friendship 4 was the only boat anchored in Chippewa Harbor at Isle Royale National Park. Isle Royale is rated as the top US National Park and but has the least number of visitors of any national park because it is an island accessible only by boat or seaplane in Lake Superior.

Two members of our crew took our tender and went to a National Park Service (NPS) small boat dock at a trail head to go hiking ashore. Two members of the crew remained onboard Friendship 4 at anchor. There is no cell phone coverage on Isle Royale and VHF communication is poor near shore and ashore due to the rock ridges that cover the island. Our tender has a fixed mounted VHF radio and a navigation system so our plan was to monitor VHF on Friendship 4 in case the team ashore needed to reach us.

Mid-afternoon one of our crew members ashore fell and broke her ankle in three places. Passing hikers transported her ½ mile to the NPS dock where our crew member used the tender’s VHF radio to call Friendship 4.

Friendship 4’s much higher antenna allowed us to contact the National Park Service (NPS) headquarters about 15 NM away using VHF CH 16. VHF communication was difficult for detailed discussion, so we quickly switched to using satellite communications (the NPS headquarters has the only landline to the island).

NPS headquarters merged the USCG Sault Ste Marie into the call. Together we determined that the best course of action was for Friendship 4 to stabilize the patient, remain at anchor, and prepare the patient for medical evacuation by NPS fast boat to a hospital on the upper peninsula of Michigan, about 45 NM away. It took about 3 hours for the NPS fast boat crew to assemble, prepare the boat, and rendezvous with Friendship 4. NPS contacted the hospital. Friendship 4 followed up with the hospital to provide detailed medical information via satellite phone.

The patient was successfully transported 45 NM to the hospital along with one of our crew members as an escort, arriving shortly after midnight. They were able to re-join Friendship 4 at the NPS headquarters the following afternoon.

SAR Event #3: Panic attack – cardiopulmonary distress, Tuesday, July 30

The next day Friendship 4 weighed anchor and headed down Chippewa Bay bound for the NPS park headquarters at Rock Harbor, about 15 NM away. As we were about to exit Chippewa Bay into the main body of Lake Superior, we noticed 3 people waving to us from the NPS small boat dock at the trailhead. It was obvious that they were signaling us. We approached the dock and they asked to contact the park service for medical help for a person ashore. We put out the fenders and tried up at the tiny NPS dock.

I went ashore and assessed the patient. The marinized version of the Wilderness First Responder course that I recently completed proved enormously valuable. I was quickly able to determine that the situation was not life threatening but further medical evaluation and treatment by professionals was appropriate.

Friendship 4 again contacted the NPS headquarters and the USCG who after the previous two events in the last week were all quite familiar with us. We initially contacted the headquarters on VHF CH 16 and then switched to satellite phone immediately. We determined that Friendship 4 could transport the patient to the NPS headquarters much sooner than the NPS could get a boat crew together and get a boat to us. Friendship 4 took the patient, his gear, and 3 other members of his party onboard and transported them to the NPS headquarters. During this 1 ½ hour trip, the patient and his spouse spent most of the time on the satellite phone with doctors at the hospital on upper peninsula of Michigan. This was helpful for us to confirm my assessment of the medical condition but was even more valuable in calming down the patient and his spouse.

The park service EMT in consultation with hospital decided that the patient should be evacuated to the hospital in Michigan. It was not overly urgent so a regularly scheduled ferry that was departing soon after our arrival transported the patient to the hospital.

Lessons Learned and Observations

- Satellite voice communications were the primary means of communication in all 3 SAR events. Friendship 4 has a KVH satellite voice & data system with a tracking dish antenna that was rock solid and robust.

- ROBUST communications with multiple organizations (boats, ashore at the scene, headquarters, hospital, etc.) were key.

- Robust communications will likely require a communications watchstander to handle the volume of communications.

- The on scene SAR coordinator should be the boat or unit with the best communications and crew size to handle the volume of communications and other actions required for the SAR.

- VHF on tender was very useful in the situation where the event occurred ashore, away from Friendship 4. It seems VHF on the tender would be very useful if a vessel has to support a SAR in waters where the larger vessel cannot go.

- Handheld VHF can supplement the fix mounted VHF and enables simultaneous communications on multiple VHF channels (to separate related traffic into “nets”).

- A powerboat may have a much better height of eye for a visual search compared to a sailboat. Our height of eye on the flying bridge is 22 feet.

- A voice recorder app on a mobile phone was excellent for capturing radio communications and discussions in the pilot house. This app was originally intended for use of a race committee member at a starting line.

- Navigation system screen capture recorded the search pattern and other information that was then provided to the Coast Guard and other authorities.

- A prepared list of US and Canadian SAR phone numbers and a map of SAR asset locations proved very useful. We should have also have listed the National Park Service land line phone number for Isle Royale.

- Wilderness First Responder course (maritime version) was EXTREMELY valuable. I wish I had taken this course years ago. I was confident that I: (a) could rapidly assess whether the situation was life threatening, (b) knew what I could and could not do on scene, (c) could treat the patient appropriately, and (d) could communicate the situation to medical professionals quickly and concisely in a manner they expected.

- Patient medical information forms were very useful. Friendship 4 requires all crew members on major voyages to fill out a standard patient medical history and patient information form (a standard form used by primary care providers). This form includes emergency contact and primary care provider contact information as well as medical insurance information. Crew members put these forms in a sealed envelope in case of emergency. In event #2, the broken ankle, we sent this form with the patient along with our written assessment. This was very useful when the patient arrived at 1 AM at the hospital. In event #3, the panic attack, we filled this information out on a blank form before transferring the patient to the NPS EMT.