Planets Can Fool You: Even in Celestial Navigation

Three Star Fix

“Safety Moments, presented at CCA Stations and Posts”

By Chuck Hawley, San Francisco Station, May 2021

For many decades, Transpacific Yacht Race navigators were required to use celestial navigation to find their way to Hawaii. There were several reasons for this:

- Electronic navigation had not been invented, or was not affordable for yachts (Omega, Loran-A).

- Electronic navigation was available, but its use was prohibited by the Notice of Race so that navigators were forced to use traditional methods.

- Loran C, which worked wonderfully along the West Coast, worked very poorly as one approached Hawaii due to poor crossing angles.

- Even early satellite navigation (Transit) provided only periodic fixes which had to be augmented with dead reckoning, although the SATNAV generally did the DR between fixes.

|

Example of a popular Loran-C which would have been a good backup to GPS, until the Loran-C system was decommissioned and the antennas were removed. |

Even using the sun to navigate to Hawaii in the summer has an odd quirk: Since you’re sailing to harbors which lie between 21 to 23 degrees north latitude, and since since the declination of the sun is also about 21 to 23 degrees north, navigators quickly discover that the sun is directly overhead at noon, leading to perplexing noon sights and a limited ability to determine one’s latitude with any accuracy. It does, however, allow you to find yourself on a “circle of position”, but that’s a topic for another safety moment.

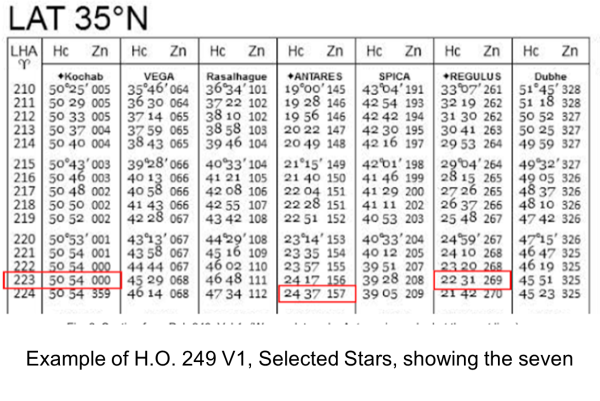

However, a summer passage to Hawaii is an excellent time to learn to do a three star fix, using H.O. 249 Volume 1, Selected Stars. In 1982, while sailing in the Singlehanded Transpac from San Francisco to Kauai, I decided that I would teach myself how to do three star fixes using Selected Stars. The concept is that you “enter” the tables with some information about where you are and the expected time of dusk or dawn, and the tables provide you with about seven of the 57 so-called navigational stars. Those stars are not necessarily the brightest in the night sky, but are distributed in such a way that they provide good crossing angles for your lines of position. Three of the recommended stars, as I recall, were in bold type, and were therefore the best choices.

So, I found myself in mid-Pacific, sailing a 4,000# boat, and boldly aiming my sextant in the direction and altitude which should allow me to pick a star out of the darkening sky. You only have about 15 or 20 minutes to find the stars and record their altitudes and the time of the sight since the horizon begins to fade from view, which leaves you without a reference point from which to measure the altitude. I managed to get the first two stars with relatively little effort, but the third star, to the south, took more searching. Finally I found it, jotted down the time and altitude, and retired to my cramped cabin to pour over the information.

|

Example of H.O. 249 V1, Selected Stars, showing the seven recommended stars for some time and place. |

To my great dismay, my three star fix put my position about 60 nautical miles south of my dead reckoning position. This was distressing, because I had no reason to doubt my DR, other than the previously-mentioned challenge of finding one’s latitude when the sun is directly overhead. To make matters worse, in a few days I was going to make landfall on a chain of islands (Hawaii), where, under the right conditions, it’s possible to sail between them and not see them, or not know which island you were approaching. I vowed to do a better job the following night, but slept very poorly with the nagging image of running into an island or having to ask someone on shore “is this Kauai?”

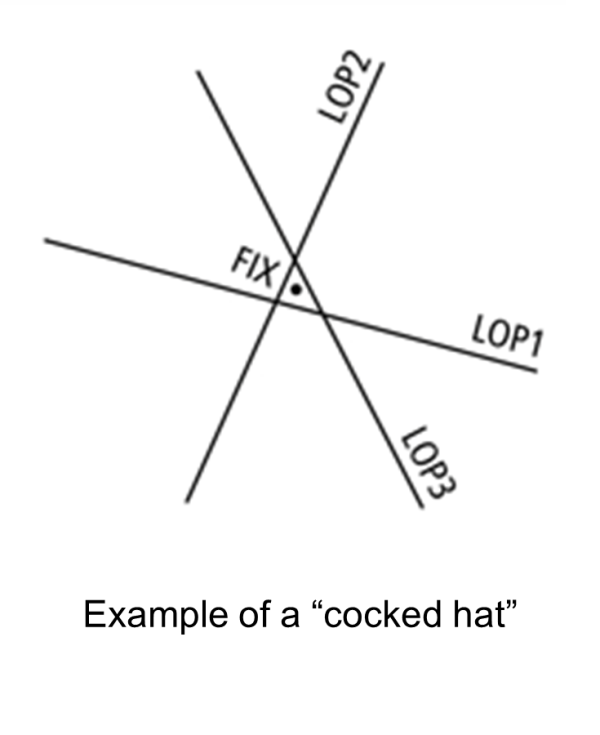

|

Example of a “cocked hat” showing where you are likely to be based on three star LOPs. |

The following night I used the same stars, the same plastic sextant and Casio watch, and the same process. Although I had traveled an additional 180 nautical miles towards Hawaii, the measurements were largely the same. Again I went into the cabin and plotted the three lines of position, and once again came up with a fix that was about a degree south of where I thought I was. To clear my mind, I went back into the cockpit and looked at the night’s sky.

Near the place where I had been shooting the third star, another slightly dimmer star also appeared, about two finger-widths away. While clearly not as impressive as the brighter star, it was one of the earlier stars to show in the night sky, and it appeared to be where my selected star would be, had I not been lured away by the brighter object.

Another trip to the cabin, and a quick glance at the Nautical Almanac provided the answer. I had been taking my third sight on a planet, probably Mars or Jupiter, which got my attention by showing up earlier in the evening, but in about the right place as my intended star. This caused me to doubt my DR position, and the ensuing upset stomach for the next 24 hours or so.

Bottom line: Navigation is the art of combining information from different sources, with different degrees of reliability, and trying to come up with the best possible answer of where you actually are. When there’s a conflict between navigational inputs, it behooves you to ferret out the truth from fiction so that you can continue safely.

The Cruising Club of America is a collection of passionate, seriously accomplished, ocean sailors making adventurous use of the seas. All members have extensive offshore boat handling, seamanship, and command experience honed over many years. “School of Hard Rocks” stories, published by the CCA Safety and Seamanship Committee, are intended to advance seamanship and help skippers promote a Culture of Safety aboard their vessels