EPIRBs, PLBs, AIS Beacons, Trackers, and Strobes

Getting Attention When You Need It

“Safety Moments, presented at CCA Stations and Posts”

By Bill Ballard, Florida Station

On February 29, 2024 Cruising Club of America published on its website, https://cruisingclub.org, its new Coastal and Offshore Communications Guide. Forty-four pages in length, it provides a comprehensive and well-organized guide to selecting, installing, registering, and using the electronic equipment that enhances the ability of the operator of a vessel to navigate, communicate, and to obtain assistance in an emergency. This paper focuses on equipment that the survivor of a capsized or sunken yacht, or a person who has become a man overboard, can use to guide a rescuer to his or her exact position before exposure to the elements renders the rescue effort moot.

The story of Kirsten Neuschäfer’s rescue of a fellow competitor, Tapio Lehtinen, in the Southern Indian Ocean during the 2022 Golden Globe single handed, non-stop, round-the world race was told in an interview with Kirsten published in the CCA’s 2024 edition of Voyages. The Golden Globe Race organization has published online a detailed report of this incident titled “2022 Golden Globe Race lifesaving regulations, Asteria sinking, lessons to be learned.” According to this report, Lehtenin’s EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon, described later in the article) got off one message as the boat went down, likely still attached to the sinking vessel. That message was sufficient to start this successful rescue.

On July 20, 2023, The Royal Prince Alfred Yacht Club (AUS) published “Review Report | Capsize of the Racing Yacht Nexba.” On July 3, the co-skippers of a new Farr 30 state of the art offshore racing sailboat came close to perishing a few miles off the Australian coast south of Sydney after the yacht’s keel inexplicably broke off from the hull. Nexba’s 180 degree capsize was sudden. The EPIRB was trapped in the boat. The crew’s PLBs (Personal Locator Beacons) were unavailable or damaged during the incident. Despite having all required offshore safety equipment, and despite having filed the equivalent of a float plan and being tracked by AIS, they spent nearly 14 hours clinging to the appendages of the capsized hull before they were taken aboard a rescue boat. This Review Report is readily obtainable through an online search.

The detailed reports on the losses of Asteria and Nexba are invaluable. It is noteworthy that Lehtinen’s portable YB3tracker provided updated positions of his liferaft to the rescue system. (YB3 is a portable Iridium (satellite) transmitter that is used to track the position of racing sailboats.)

Equally noteworthy was that it was 12 hours after Nexba’s capsize before a distress message actually reached the Australian rescue system. This occurred after one of the co-skippers was able to use her smartwatch with GPS to inform the Australian emergency service of their situation and position. Both these incidents illustrate the fact that yacht safety equipment is useful only to the extent it can be accessed in difficult conditions, that it is in working order, and that the operator is thoroughly familiar with its operation. They also illustrate that guiding a rescue vessel into the vicinity of survivors in the water or in a life raft is not the end of the rescue problem. There remains the problem of visually spotting the victims among waves or swells, often in low visibility conditions. This last problem is the reason that recently offered EPIRBs and PLBs incorporate both a 406 MHz satellite Lat/Lon to bring the rescue operation into the vicinity of the victim and a 121.5 MHz homing beacon, an AIS Lat/Lon, plus a strobe light, to assist rescue forces in establishing visual contact.

EPIRB – Electronic Position Indicating Radio Beacon. All EPIRBs activate automatically when out of their bracket and floating. When activated manually, or automatically when floating in water, an EPIRB will broadcast on a 406 MHz frequency a distress message in short intervals for 48 hours. This message will include its unique 15 digit identifier number and its Lat/Lon. This transmission is the entry point into the Global Maritime Distress Safety System (GMDSS). The US system that receives the distress signal is operated by NOAA and is called SARSAT (Search and Rescue Aided Satellite Tracking). SARSAT is part of the GMDSS. EPIRBs and Personal Locator Beacons, (PLB) must be registered at www.beaconregistration.noaa.gov. The completed registration provides information necessary to rapidly initiate a search. The contact persons listed in the registration are important players in this system.

Beginning July 1, 2023, all EPIRBs for specified commercial and passenger vessels must incorporate GNSS capability and Automatic Identification System (AIS). GNSS refers to a constellation of satellite systems that provide positioning, navigation and timing on a global or regional basis. These constellations, which are maintained by multiple cooperating nations, provide greater coverage, more rapid positioning, and greatly improved accuracy over earlier iterations of the US GPS system.

Recreational vessels are classified as voluntary users and are not required to have an EPIRB. They may use older, less capable EPIRBs; however, batteries need to be replaced at the recommended time interval, frequently 5 years. Some units require that replacement be made only by an authorized facility. A Category I EPIRB is required on all passenger vessels and other commercial vessels 65 feet or longer. Category I and II are differentiated only by their bracket. Category I has a protective shell which will eject the beacon to float to the surface if the boat sinks. Class II stores the beacon and prevents accidental activation.

AIS (Automatic Identification System) transmits information about vessels of all sizes. It operates within the VHF marine radio frequency band. AIS receivers, available integrated into VHF radios at moderate additional cost, provide a chart plotter the position, speed and heading of all vessels that have AIS transmitters. Most smaller vessels do not have AIS transmitters, so look-out and radar are still primary. SIMRAD offers this guidance: “Summarizing [ColRegs Rule 5 (Look-out)], if you have operational radar fitted, you should be using it as a part of your watch keeping and collision prevention activity.”

DSC (Digital Selective Calling) is an older VHF system which, with a Lat/Lon feed from your GPS, can send an emergency text message with your Maritime Mobile Service Identity (MMSI) and your position to another DSC enabled radio. That radio will sound an audible alert. The caller in distress should elect 25 watts output if available. Tall antennas can pick up this signal from about 30 miles away. The DSC system requires some practice. There are some good videos to help with learning this system. More than one person on a vessel should be trained to use DSC – the skipper may be incapacitated. In coastal cruising, with many vessels within a few miles of the vessel in distress, assistance may be received more rapidly through DSC than through satellite monitoring systems.

To use DSC or AIS you must register an MMSI with the FCC. If leaving US waters, your boat will also require an FCC radio station license. BoatUS and US Power Squadron offer their members free issuance of MMSI numbers and registration with the FCC. However, if you intend to visit foreign countries, you must obtain your MMSI number directly from the FCC. If you had a prior MMSI, it must be canceled. The required form is FCC Form 605. Contact the FCC at fcc.gov/about/contact.

I urge everyone to read on the internet “Advancements in Boating Rescue Technology by Vincent Daniello” www.boatsafetymag.com . I have quoted Mr. Daniello throughout this article. His article was written in 2012, but it has vital information about the SARSAT system and, for recreational vessels, discloses its weakest link. 96% of EPIRB signals are FALSE. Deployment of SAR units may be delayed while the shoreside team attempts to “verify that the signal is intentional.” If the emergency contacts listed in your EPIRB/PLB registration are not available or have no knowledge of your plans that day, the verification process may be delayed.

The 2023 model EPIRBs include a Return Link Service (RLS) that confirms the distress message was received. This lets the skipper focus on the problems at hand. Another new feature is Near Field Communication (NFC) – a link to a smartphone app to monitor battery state and perform other functions. These units also have an AIS alert via VHF to nearby vessels equipped with AIS. Lastly, they will have a visible and an infrared strobe to assist the SAR unit in making a close final approach.

PLBs, PABs and other MOB Devices

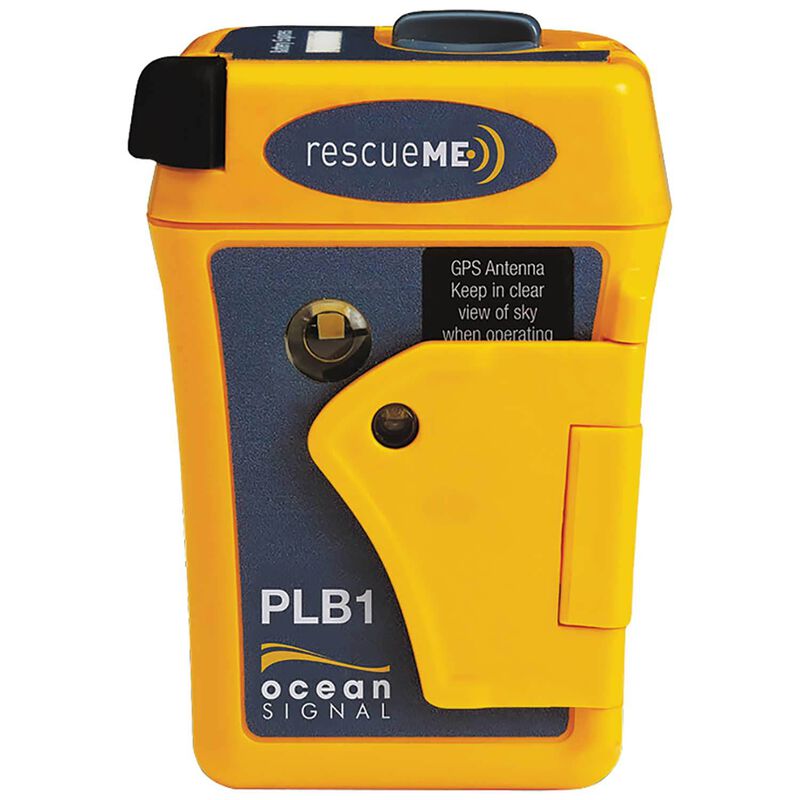

PLBs (Personal Locator Beacons) are essentially small EPIRBS that can replicate the functions of a vessel’s EPIRB for a person alone in the ocean. Some are small enough to occupy a pocket in an inflatable life vest. Battery life is about half that of an EPIRB for a vessel. Unlike an EPIRB, PLBs are not required to float. The user must hold the unit with the antenna vertical and above the surface. The PLB antenna may require unfolding or unreeling. The antennas can be broken or fouled by the wearer’s clothing or inadvertent actions. A PLB transmits a distress signal at a 406 MHZ frequency into outer space. It must be registered with NOAA. A Personal AIS Beacon (PAB)[1] will have a unique identifying number (an MMSI) and must be separately registered with NOAA.

A Personal AIS Beacon (PAB) transmits its distress signal and position information on 121.5 MHz, a line-of-sight transmission with about 5 nm range. Its goal is to obtain assistance from nearby vessels - including the vessel an MOB departed from. Per Landfall Navigation, a PAB, which Landfall sells, does not require registration. However, the PAB may be useless unless the rescue vessel has a VHF marine radio with an AIS receiver which is feeding the PAB’s AIS data to a chartplotter which is being monitored at the helm station. (Personal AIS Beacons are given many names in articles and catalogs. We prefer this term, and the initials PAB to differentiate them from Personal Locator Beacons. Note that PABs all transmit on AIS frequencies, but not all transmit a DSC message was well.)

An article, “Electronics for Man Overboard Alert” at saltwatersportsman.com describes a variety of new devices such as an “electronic tether.” It uses a Bluetooth connection between the recently departed and his or her boat, each equipped with a small device, to sound an alarm and stop the engines. Relatively inexpensive and no registration required - range is measured in feet.

There are many MOB scenarios, all of which can be addressed with money, persuading people to wear bulky equipment, faith in gadgets, and a personal proclivity to test every safety gadget at recommended intervals. A small, simple, and tough MOB strobe is more likely to be worn constantly than would a multi-function PLB. The Weems and Plath Personal Rescue Strobe is one example. No paperwork. In most situations you are going to get alongside the MOB in time to save a life. The greater problem for most boats is getting that person up and into the boat without further injury. However, if you are a single hander watching your boat sail away, a registered, regularly tested, PLB is likely to be your best and only friend.

Chuck Hawley, SAF, and Frank Cassidy, GMP, assisted in the preparation of this paper.

The Cruising Club of America is a collection of accomplished ocean sailors having extensive boat handling, seamanship, and command experience honed over many years. “Safety Moments” are written by the Club’s Safety Officers from CCA Stations across North America and Bermuda, as well as CCA members at large. They are published by the CCA Safety and Seamanship Committee and are intended to advance seamanship and safety by highlighting new technologies, suggestions for safe operation and reports of maritime disasters around the world.