A Note on Hypothermia

MEDICAL MOMENT: HYPOTHERMIA

by Bill White, MD

Member of the CCA Medical Advisory Committee

It is Fall, and the air can be crisp and clear with a brisk breeze blowing. A perfect sailing day. A word of caution is needed here. One would be wise to consider the possibility of hypothermia. However, do not ignore the possibility of hypothermia even in warmer conditions such as when cruising to the Caribbean or sailing in the Gulf Stream during the Bermuda Race. Prolonged exposure even in mildly cool conditions can put you at risk. To understand hypothermia is to know how to avoid it and how best to treat it.

Hypothermia is defined as a core body temperature less than 95 degrees Fahrenheit. Core body temperatures less than 90 degrees are considered moderate hypothermia, and less than 82 degrees are considered severe and life threatening. Becoming hypothermic means you are losing body heat faster than you can generate it. Body heat can be lost by three basic methods: conductive loss, evaporative loss, and radiant loss.

Conductive loss is what happens when you are immersed in water. It happens faster in cold water but can even happen in the warm waters of the Gulf Stream.

Evaporative loss is what happens when water on your skin uses the heat from your body to evaporate. If the air is dry, the evaporation happens more quickly and saps more of your body heat.

Radiant loss is the heat your body gives off to the air around you. The colder the air the faster you lose heat. Once your core body temperature falls below 95 degrees Fahrenheit you have become hypothermic. Before that you may be cold stressed, but not actually hypothermic.

How is sailing a setup for hypothermia? A day that starts in sheltered waters with warm temperatures on land may make you feel like you don’t need to wear a lot of warm clothes or even bring foulies with you. Once you leave port and clear the shelter of the land, the sea state can change. Pretty soon you find out you aren’t dressed for the occasion. You are getting wet from spray, you aren’t wearing foulies, you don’t have enough layers, and you are starting to get cold. If you don’t address this soon you may be headed down the road to hypothermia. It can be especially dangerous if you are a solo sailor as there isn’t anyone else aboard to help you out.

What do you do? The first step in treating hypothermia is to prevent it. Make sure you bring more gear than you think you’ll need. Having a good set of foulies on board plus some extra layers such as fleece pants and a fleece top are very good ideas. Fleece and wool both continue to help reduce conductive and radiant heat loss even when wet. Consider wearing long underwear as a base layer. If you are too warm you can always take it off. You should remember that the warmest part of your day may be the time before you leave the dock. Don’t be deceived. Bring enough kit and maybe even a little extra just in case. Avoid cotton clothing. When it gets wet it will hold moisture without providing much insulation. This will prolong evaporative heat loss and will provide little protection against conductive heat loss. Lastly, bring a watch cap and make sure you have gloves that will keep your hands dry and warm.

What if you notice you are getting cold stressed? Cold stressed is when you feel cold and you may even be shivering, but your mind is still working well and you are able to make clear decisions. Your coordination is still intact. This is the time to make an intervention. Get wet clothes off and put on dry layers. Get your foulies on, or at least something windproof to help reduce conductive and radiant heat loss, particularly covering your head with a beanie or watch cap. Get active to help generate body heat. Drink warm fluids and take some nutrition. When your body starts to shiver it uses up energy quickly and will need the fuel to keep you going and help get you warm. If possible, remove yourself from exposure to the elements. Go down below and get warm. Be sure to keep an eye and other crew members to make sure they are not heading towards hypothermia. The key here is early intervention to avoid progressing to true hypothermia.

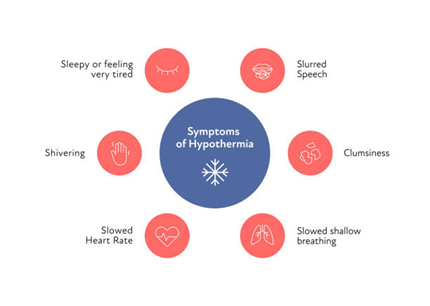

What is true hypothermia and how do you recognize it? Unfortunately, it is not as easy as taking someone’s temperature. A thermometer under the tongue may not be an accurate representation of someone’s core body temperature. You are better off gauging hypothermia by how someone appears and how they are acting. As someone gets truly hypothermic, they begin to lose the ability to think clearly. They become uncoordinated and lose strength. As this progresses, they may develop bizarre behavior such as taking off clothing despite being cold. Shivering that started when they were cold stressed will become severe and uncontrollable. As the body temperature drops further, vital signs become depressed, the person becomes less responsive, and shivering eventually stops. These are very worrisome signs. The cessation of shivering means that one’s body has lost its ability to actively rewarm itself. The affected person is no longer able to make decisions to help themselves or take actions to get themselves warm. They can no longer perform their duties as a crew member. In short, they have become a casualty and must be cared for by the remaining crew. This has now become an emergency situation and the person’s life may indeed be threatened.

Treating true hypothermia is not as simple as telling someone to get active and warm themselves up. This may work when one is cold stressed, but in true hypothermia, coordination is decreased, strength is decreased, and judgement may be impaired. If someone is truly hypothermic, they need to be managed by other crew members until they are warm again. Remove them from exposure. Remove wet clothes and replace with dry layers. Wrap them up like a burrito in blankets and a vapor barrier. If needed, put a warm person in the burrito with them. Be careful about giving food and water until you know the person is alert and conscious enough to swallow without choking or aspirating.

Fortunately, it is relatively easy to prevent the situation described above. Prepare each time you put to sea. Take what you think you will need and then take some extra gear in case you or someone else on the boat need it. Recognize the signs of being cold stressed both in yourself and in others. Address them early and aggressively before they progress. That will give you the freedom to enjoy your time on the water in comfort and safety.

[Editors' Note: We highly recommend printing out and carrying the "Cold Card" containing a concise summary of symptoms and treatments for hypothermia. You can find it here.]

CCA Medical Advisory Committee

Jeffrey S. Wisch, MD, Fleet Surgeon, Chair, Paul Kanev, MD, Anne Kolker, MD, Moe Roddy, RN, Charles Starke, MD, Bill Strassberg, MD, Bill White, MD